GUEST: The Honorable George W. Ball, Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs

CORRESPONDENTS: Howard K. Smith, Bill Downs, Stuart Novins

You are AT THE SOURCE.

Appointed by President Kennedy shortly after his inauguration, veteran international lawyer George Ball is primarily responsible for the development and conduct of US foreign economic policy. Yesterday, however, it was reported that Under Secretary Ball had risen to become the No. 2 man in the State Department. To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the critical problems and objectives face by Under Secretary of State Ball, he was interviewed by CBS News Correspondents Howard K. Smith, Stuart Novins, and Bill Downs.

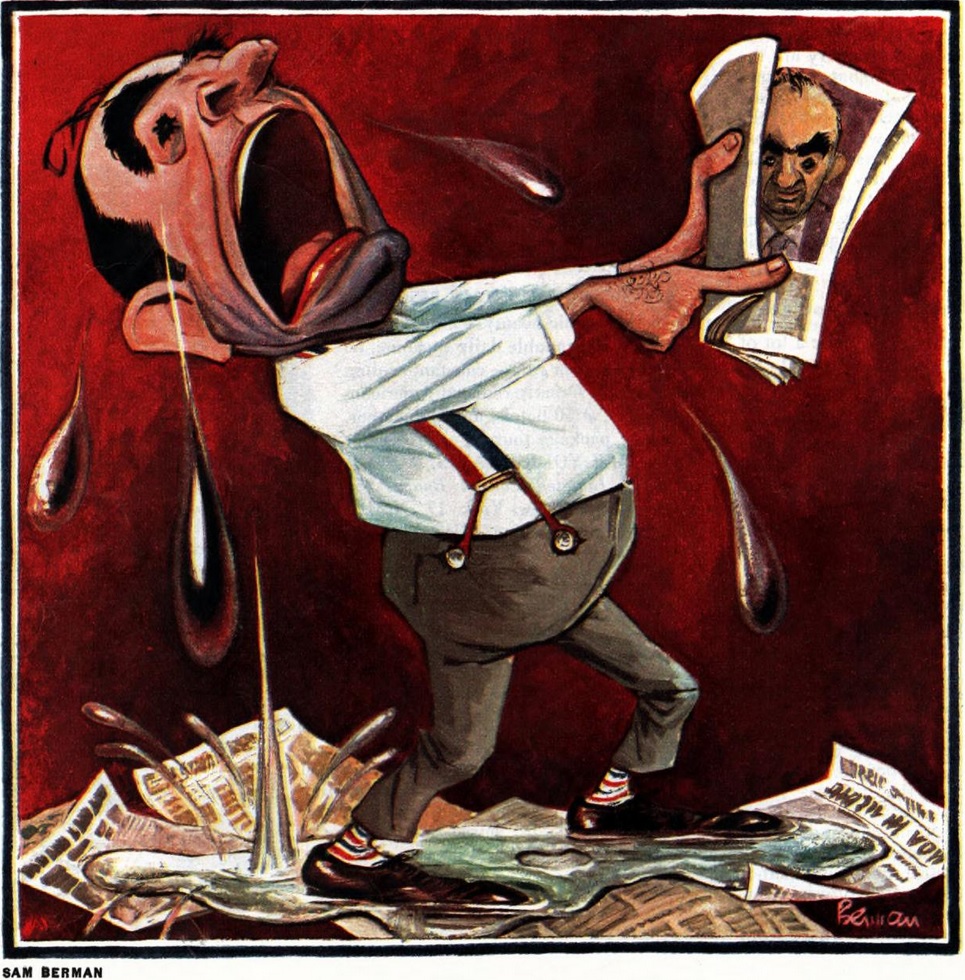

MR. SMITH: Mr. Ball, a columnist wrote about you and said "George Ball, whose gift for decision and dispatch long ago commended him to President Kennedy, has become the No. 2 man in the State Department in all but name."

Is that so?

MR. BALL: Well, I'll tell you, Mr. Smith, I normally believe what I read in the newspapers and I particularly believe what columnists write; but this story doesn't happen to be true. Mr. Bowles is the No. 2 man in the State Department. He is the Under Secretary of State. I am the No. 3 man, I am the Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs.

Now I think to the extent that there may have been some misconception of this, it arises from the fact that Mr. Bowles has been away a great deal, I am away from time to time; when one of us is away, the other pitches in. We all have so much work to do in the Department these days that with the Secretary, Mr. Bowles and I consider ourselves as available for whatever task may come along. The result is that I haven't confined myself strictly to economic matters and he hasn't confined himself strictly to political matters.

MR. DOWNS: Well as Under Secretary for Economic Affairs, Mr. Ball, you are in charge of the New Frontier's revolution for rising expectations. That has almost become a cliche in this Administration. Just what does the phrase mean, "revolution of rising expectation?"

MR. BALL: Well, it is a rather vivid phrase, isn't it? It is a phrase that suggests a situation which is a very complex anatomy I would suppose. After all, there are about three billion people in the world. One billion of those people live in countries that have per capita—where per capita annual income is fifty to a hundred dollars, really fantastically low. Now, in the last few years, as a result of the wars which have broken the old social and political fabrics as a result of the increases in technology and communications, these people are breaking free from the old systems. Whether they have lived under colonial arrangements which have been shattered by events, whether they have lived in countries which have simply been dormant for hundreds of years, they are now beginning to want and to feel that they are entitled to enjoy the kind of rich life which the people in the industrialized, economically advanced countries enjoy, and they are going to get it. If we help them, they are going to get it faster and probably are going to get it in a way which will insure their freedom and independence. If we don't help them, they may get it in ways which will insure that the frustration of some of their expectations, their delivery into systems which will mean tyranny and oppression and possibly that they will be swept into the vortex of the communist orbit.

MR. NOVINS: Mr. Ball, in that connection you made a speech recently before the Foreign Press Association, and in it you emphasized our commitment to the United Nations and our commitment to this revolution of rising expectations.

Why is it that we don't use more than we do—the U.N. channels for our assistance? Why don't we—

MR. BALL: Well, to some extent it's done through the special fund which Mr. Paul Hoffman administers, which does a great deal of pre-development survey work, the technical assistance programs under the specialized agencies of the United Nations. It's a mixed arrangement which we have for the administration of aid. The great part of it goes directly on a bilateral basis from the United States, but there is also the World Bank to which we subscribe, the International Development [Association], the Inter-American Development—all kinds of different administration.

MR. NOVINS: Well, are we concerned, Mr. Ball, that we are not going to be able to put strings on our aid if we do it through international bodies?

MR. BALL: Oh, no, that's not the problem. Actually, in some ways international bodies can take tougher lines than when aid is provided bilaterally.

But it's simply a matter of the requirements of a given situation. For political or other reasons it's much more desirable to provide aid on a bilateral basis. In some countries the multilateral provision of aid becomes more effective.

MR. SMITH: Mr. Ball, could you interpret for us the President's famous statement to the effect that we will give attention and consideration to the needs of countries that share our view of the world crisis. Is that a new principle?

MR. BALL: No, I think that that has been somewhat misinterpreted. Actually the President, I think, in his last press conference clarified that phrase to a considerable extent.

What the President said in his last press conference, and what he said repeatedly, and what we've all said, because this is the view of the Administration, is that we are interested in providing assistance to these countries and exporting capital to help them. Our interest in seeing that they are able to reach a point of economic development in an atmosphere of freedom which will assure both their political and economic independence.

Now, this doesn't mean that they have to copy our pattern of organization of their society, or that they have to share our views.

What we want them to do is to be independent, because we are convinced that a viable independent society will be a society which will resist the pressures from that—

MR. SMITH: Still, we are not happy about Mr. Tito's speech at the Belgrade Conference of Neutrals, are we?

MR. BALL: We have always known that Mr. Tito was a communist—there has never been any question about it. The only difference between Mr. Tito and some of the other satellite countries is that Yugoslavia is not a member of the bloc, that it pursues different means to the long communist objective.

But, at the same time, it maintains its independence, and this is the important thing.

MR. DOWNS: Well, Mr. Secretary, you have also said that the Free World and America are not providing enough of this aid.

How much is enough?

MR. BALL: There is no measure that is enough. I mean, this task that we face is a fantastically great task. Obviously the resources of any country, even a great country like ours, are finite. We can only provide a certain quantum of aid which we hope will enable countries, by self-help, by mobilizing their own energies and resources, to make ultimately a breakthrough to the point where they can be independent and self-sustaining.

MR. DOWNS: Are you saying that this is a great big international gamble for civilization, or something like that?

MR. BALL: It's a great gamble in which not only the United States but all the Western Powers are engaged. Actually this is a cooperative effort now, and we have made great strides in bringing this about.

MR. SMITH: Is it sufficiently cooperative? Your predecessor in this, in your job, who is now the Secretary of the Treasury—

MR. BALL: I just had lunch with him.

MR. SMITH: —tried to get the other allies to share in—

MR. BALL: We have been continuing this effort with some considerable success.

MR. SMITH: And you are satisfied with what they are doing?

MR. BALL: We are never satisfied, Mr. Smith. But we are certainly aware of the fact that they are making a much larger effort, many of them; that we are now enabled to tie together the things we are doing in a cooperative effort and to eliminate duplication and to insure maximum effective use of resources in a way that we haven't done before.

MR. NOVINS: Mr. Secretary, let me take advantage of the fact that sometimes in the absence of others you slip into the political field.

On August 13th the East Germans started to build a wall. Why didn't we knock it down then?

Mr. BALL: Well, you know, the wall, in many ways, Mr. Novins, was the great symbol of the defeat of Soviet policy. If the Soviet policy had been successful, they wouldn't have needed a wall, they wouldn't have needed to engage in all these exercises which they are engaging in over the whole Berlin situation. But they haven't been successful. They couldn't stand the out-pouring of thousands of people a month away from their system, escaping from it, so they had to build a wall. Now, they built a wall in East Berlin. You can see the difficulties of trying to break the wall down. It stands as a symbol of the defeat of their policies.

MR. NOVINS: Well, we are told that in West Germany there is more concern about the fact that we did not break it down than there is about the fact that the East Germans built it.

MR. BALL: Well, we have developed, with our allies, we are in the process of developing a whole strategy of meeting the problem of what we might call the kind of Berlin offensive which the Soviet Union has mounted. The wall is one aspect of that. This policy is an elaborate policy—it calls for response to particular moves. These moves are all well worked out.

Now, when the wall was built—this was something where you have to make a judgment—is this—do you want to move tanks through this wall and smash it down at the risk of a war which would be immediately exploited?

We had to determine the point where we make the ultimate stand. And this was a case where in the long run I think the construction of the wall is going to cost the Soviet Union a very great deal in terms of showing to the world—

MR. SMITH: Now, many people consider that the building of the wall was a blow to us. You consider in fact that it is a blow to the Russians?

MR. BALL: Well I think it has both effects. I mean it has certainly caused a good deal of concern and dismay. At the same time it symbolizes their defeat.

MR. DOWNS: Well, George, doesn't this bring up the whole problem of—is aid the answer? When the Russians started testing and started throwing around these super bombs, immediately our neutral friends sort of allied us with raw power, although we have not used power as such in that way. Maybe if we took all of this foreign aid and put it into super bombs perhaps we could achieve our goals more rapidly. Do you think that—

MR. BALL: No, no. You know the policy of aid which we follow has been extremely successful. The fact is that the Soviet Union has made almost no gains in the past few years in the form of bringing within their orbit new nations. They have invested a great deal of money, they have spent a great deal of effort—

MR. DOWNS: Cuba?

MR. BALL: Cuba is one of the few exceptions I would think.

MR. DOWNS: Laos?

MR. BALL: Laos is undetermined as of now. But, if you think of the magnitude of the effort they've made, they've also engaged in great foreign aid programs, many of which have been quite frustrating to them. But the significant thing that we have succeeded in doing is in giving these countries the ability to be independent.

Now, when they are independent they may adopt a course of neutralism, of being disengaged from the cold war struggle itself, they are concerned with their development, they may say things which we don't wish them to say which—views that are unpopular with us, but they stay independent which is the significant thing in the sense that they are not—do not become simple tools of the Soviet Union.

MR. DOWNS: We have been fostering and supporting the idea of a common market which is now going to become a major competitor of the United States. Isn't our policy in this sense self-defeating?

MR. BALL: Well, actually I think that the development of the European Common Market is one of the great successes of our policy, just as some of the things that the Soviet Union is doing now are symbols of the defeat of theirs.

After all, if you think of Western Europe as it existed for hundreds of years, states which were engaged in warfare, in always being at one another's throats, three times in 75 years France and Germany were at war. Now we have something which is a very old dream which has been brought into practical reality, the beginnings of a kind of United States of Europe. This is the way that many of the Europeans think about it. I think it is about to be enlarged if the present negotiations are carried on into a state of modern dimensions. Now you say it will be competitive with us, it will be a great market for us. Of course we are not afraid of competition. If Western Europe becomes healthy, economically healthy, we will prosper by it.

MR. NOVINS: Mr. Secretary, could we take that one step more. The NATO Alliance as a military alliance is from an economic point of view negative. I mean it doesn't produce.

MR. BALL: Well, it's not intended to be—

MR. NOVINS: No, of course not. On the other hand the Common Market is something that is a positive factor. We belong to NATO. We don't belong to the Common Market. What would be the United States attitude toward an expansion of the NATO Alliance into something more like an Atlantic Community that would involve economic activities? Would we be part of that?

MR. BALL: Well, the NATO Alliance is specifically a defense alliance, directed at defending—

MR. NOVINS: But it's there.

MR. BALL: —against exterior menace. The Common Market is not by definition a defensive arrangement. This is an arrangement where people living next to one another are joining together, pooling their economy, so to speak, in order to become economically stronger. At the same time they are building a structure of institutions which gives them the beginning of a kind of political integration. Just as in our country we gathered together 50 states in a common market, if you think of the United States as a common market of 50 states, then you could think of Europe as a common market of what may become 15 or 16 or 17 states.

MR. NOVINS: What I am reaching for, Mr. Secretary, is what the United States attitude is, or is likely to be, toward something similar to what Senator Fulbright talked about, a concert of free nations, and I mention NATO only as something which exists and which—

MR. BALL: Well, I think politically that we can go very far in strengthening the bonds that tie to us to the nations on the other side of the Atlantic.

MR. NOVINS: In what direction?

MR. BALL: We can, and I think we must—we have already, through the OECD, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which has just come into being. It's an extension of the Old Organization for European Economic Cooperation. We are a member of that, as Canada is, and we are working with the Europeans on developing common economic policies and on working together toward providing aid toward underdeveloped countries, and working together to help solve some of the difficult market problems in the world.

Now, this is practical cooperation in the Atlantic Community of a kind we haven't had before in the economic field.

MR. SMITH: In this connection, the Congressional Quarterly, which is much read in this Capital, had a piece recently which said that the Berlin crisis is hiding the fact that there is going to be a crisis over America's foreign trade policy. The powers wanting protectionism are getting so powerful in Congress that we are going to face a fight over whether we can continue the liberal trade policies of the past.

MR. BALL: I have perfect confidence that in the face of the new trading world which is emerging, which is a world of marvelous opportunities for an America which is willing to seize them, that while there may be the appearance of a great deal of protectionist sentiment, once the dimensions and the opportunities and the possibilities of this new emerging world are understood, that we will adopt a liberal policy, a liberal trading policy, as we must. After all, our country has a very large favorable trading balance in the world, and even though our total balance of accounts may be adverse, our trading balance, our merchandise balance, is favorable.

It would be the height of folly for us to turn in on ourselves and be fearful of trading with the world and become protectionist, and I don't think we ever will.

MR. DOWNS: Mr. Secretary, if we could look south of the border again, there is the Alliance for Progress which is the Kennedy Administration's most ambitious thing that they have initiated.

Will this Alliance, do you think, be able to meet the challenge of Castroism? It hasn't, so far.

You were talking about reforming not only economies, but reforming governments, so that one junta or dictatorship of a small family or group of companies, does not run a nation.

Is this the United States' business? Can we do anything about it? It's been the pattern there for centuries.

MR. BALL: It's a very big concept, Mr. Downs, the Alliance for Progress, and it includes many different kinds of activities. But what it chiefly provides for is arrangements whereby we will help these countries to try to bring about the sort of reforms which are very long overdue, reforms which mean the breaking down of old rigid caste systems and their society, social structures, where a decent distribution of their resources can be obtained, where there could be such things as farm cooperatives developed, or there can be credit provided for self-help housing, where the poor worker in these countries can have a chance for the first time in his life.

Now, there is bound to be a good deal of resistance to this, because we are undertaking something of very, very great importance.

MR. DOWNS: A very touching thing, because this is exactly what Khrushchev is trying to do to the United States.

MR. BALL: Well, this I would hardly admit. I mean, what we are trying to do in Latin America is with great consent of the Latin American people, and this is a significant thing. There is enormous enthusiasm for the Alliance for Progress in Latin America, because the people feel that this provides them with the opportunity that they have needed over the years, and what we are doing is providing them the chance, through their own efforts. The emphasis here is on self-help, as it is in the other efforts that we are making in that direction.

MR. DOWNS: Well, what becomes of companies like the United Fruit Company, the banana republics, dollar diplomacy, the old oil cartels—

MR. BALL: There will be no difficulty about a place for American private enterprise in the new Latin America. In fact, there will be far more security in societies which themselves are secure than under dictatorship arrangements, where a few dominate the many and can be overthrown every other night.

MR. NOVINS: Mr. Ball, if, assuming that you had an ideal economic regional plan for South America, and assuming that it could be implemented under ideal circumstances, as an expert on economics how long would it take before we would see any results?

MR. BALL: Well, you'd see some results from any kind of effort in a short time. Efforts are all—

MR. NOVINS: Reckoning points—breakthrough points.

MR. BALL: A breakthrough may take quite a long time in Latin America.

MR. NOVINS: Is there much time?

MR. BALL: And it must be done on a monolithic basis; it will be done. One country after another will begin to emerge, to develop, to change its own structure toward a democratic tradition, to develop its institutions, to develop the base of a strong economy. We will have successes some places, we will have failures others. When I saw "we," I'm not thinking just of the United States.

MR. NOVINS: Oh, no.

MR. BALL: I'm thinking of this working together of the United States and the Latin American states.

MR. NOVINS: Is there time for that, Mr. Ball, in view of the threat of communism, the threat of Castroism, if that is separated from communism—is there time for this? Are we doing long-range planning that there is no time for?

MR. BALL: The long range is always upon you sooner or later, you know, and actually this is a situation which you don't solve by short-term measures. If you try to solve it by short-term measures you will defeat yourself. We have to work here over a period of time. We have to build soundly; we can't improvise. This can't be a jerry-built business. We throw our money away and nothing will come of it if we do, so that what we have to do is to work on the assumption that, with the understanding and new spirit of the Latin American people, we will be able to achieve these—

MR. NOVINS: Are you satisfied that they are moving fast enough in the reforms you are talking about?

MR. BALL: I'm never satisfied, Mr. Novins.

MR. DOWNS: Well, you brought up at one point in one of your speeches, Mr. Secretary, the fact that one of the problems of instituting those reforms is that you have things like a population explosion where you barely keep even, that you don't achieve a revolution, or it's very difficult to. Now, it brought to my mind—is it possible and is this job really too big for us without regimenting whole societies, whole nations, down to the point of their breeding, how many children they can have.

MR. SMITH: I am sorry to interrupt. I'm afraid we have almost run out of time. I wonder if we can save your answer on that and cover that area in just a moment.

MR. DOWNS: Mr. Ball, can you achieve these reforms without absolute regimentation of everything?

MR. BALL: Well, if we were to regiment anything we would defeat our own ends, wouldn't we? The whole point of what we are attempting to do is to bring about a development and a transition or transformation, in effect, of the societies of many of these countries by their efforts. So we assist this, to bring this about in the conditions of freedom without regimentation.

MR. NOVINS: What will we do with a country like Paraguay?

MR. BALL: Well, Paraguay is an example of a country with very minimal resources, which is located rather disadvantageously, which suffers a great many problems.

MR. NOVINS: Also a dictatorship.

MR. BALL: At the moment it has a dictatorship.

MR. SMITH: Tell me, is it possible that Castro is a help rather than a hindrance to this, that his existence will frighten some conservative governments into reforms?

MR. BALL: I would suggest that to some extent this is true, that certainly many of the governments are aware and disturbed—aware of the potential of Castroism and disturbed by it—and that they may be prepared to take actions which otherwise they would be reluctant to take.

MR. NOVINS: I wonder, Mr. Secretary, if you would feel that it's not entirely cynical, the comment that is made by some of the Latin Americans that much of the foreign aid they are getting now they can thank Castro for.

MR. BALL: No, I don't think that's a fair statement. As a matter of fact, the attention that the United States is now giving to Latin America was overdue. And I am certain that Castro or no Castro, that when this Administration came in we would have turned our attention and concentrated a great deal on Latin America.

MR. SMITH: Thank you very much, Mr. Ball.